Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

Of course, a single piece could never suffice to describe Machiel Kiel’s life in the academic field. His unique research, marked by outstanding work and great dedication, the traces he left in archives across Europe, especially in the Ottoman Archives and the light he shed on countless historical works were not merely academic accomplishments; they were the result of a heartfelt commitment and tireless effort. Yet today, even writing a few lines after him is an attempt to express, even if only slightly, the profound sadness within me.

During his elementary school years, a teacher noticed Machiel Kiel’s struggle with letters. He was introduced to the destruction and poverty caused by World War II at a young age.

Reading was not easy for him, but his desire to learn never faded. He could not continue to middle or high school and began to walk patiently on the bumpy roads of life. He worked as a bricklayer for his father for years. He grew accustomed to stone, mortar and patience. Perhaps that’s why, as someone deeply in love with Ottoman architecture, he eventually learned to speak the language of stone and hear what the walls had to say, before anyone else.

One day, he discovered that in the Netherlands, those who speak three languages could enter university without an exam. So he took hold of life once again through the languages he knew. He worked, he persisted, he succeeded. After those days, he was no longer just a stonemason, but a chronicler of history, someone who recorded the memory of stone.

He already knew German, English and French, but he learned Turkish, Serbian and Bulgarian with great effort to understand the geography he had set his heart on. He learned not only languages, but also the history of states, the soul of nations, the memory of cities and the language of stones.

Despite his difficult childhood, he never gave up. With his own labor, he opened the doors that life had closed to him and completed his doctorate at the University of Amsterdam. He then embarked on an academic journey that took him from Utrecht to Harvard, from Moscow to Istanbul. Every university he worked at and every city he visited bore witness to his dedication to both science and art. Kiel was not only an academic in pursuit of knowledge, but also a sage tracing the past, and a man of the heart devoted to preserving the values of art.

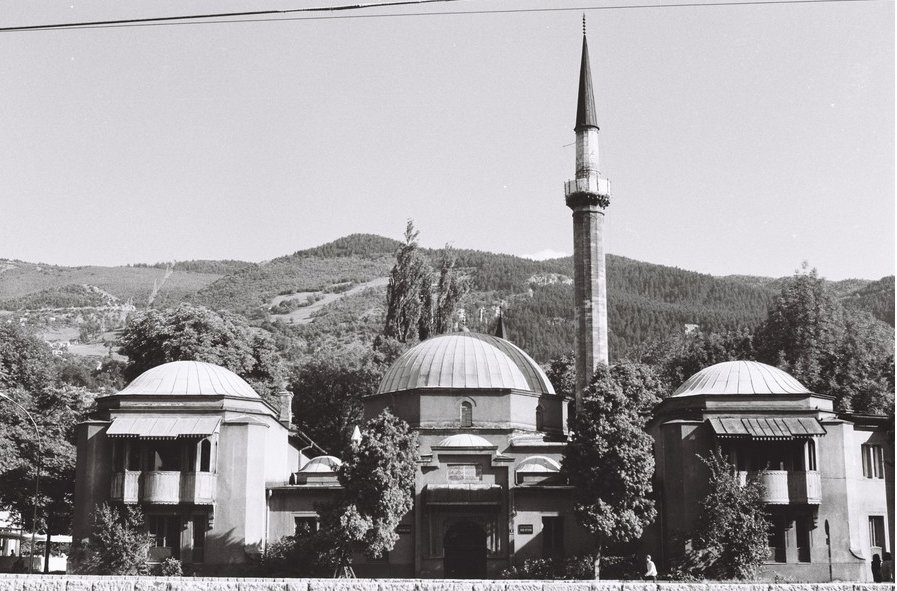

He devoted his 87 full years of life to stones, historical buildings and traces of history that were on the verge of disappearing. He searched for the memory of the Ottoman Empire in every geography, every place, every village and every city. Sometimes he recorded a fountain with running water in a lonely mountain village, an old tekke at the summit of a hill, or the stones on the minaret of a village mosque resisting time; sometimes it was the ruins of a bathhouse in the city center. Whatever he saw, he photographed and documented. But more importantly, he generously shared his knowledge with his colleagues, especially young academics.

Today, the treasured photographs, writings and memories he left behind are silent witnesses to his journey of science, art and loyalty.

One day, out of great curiosity, he put an old camera in his bag and set off. His journey led him toward the Balkans and Anatolia, where he encountered stones and ruins, the silent witnesses to the past. And this journey became a legend that shaped not only his life but also our historical consciousness, protecting our cultural and artistic values.

In 1967, at the age of 29, Machiel Kiel traveled to Albania to photograph the Ottoman monuments that Enver Hoxha had begun to destroy. With his first academic trip to Albania, a country where no one dared to go or conduct research, he marked the beginning of a lifelong adventure. Kiel lived this adventure for a lifetime and remained true to his academic integrity.

As he became familiar with Turkish art, architecture and cultural values, he became passionately attached to the multilayered cultural heritage of the vast Ottoman-dominated geography. His deep respect for Turkish-Islamic artifacts made him not only a scholar but also a brave and willing protector of this civilization.

Kiel’s lifelong research, the thousands of photographs he took, the hundreds of works, books and articles he wrote, the conferences he gave and the papers he presented at symposiums are not only academic contributions; they are also valuable products of a great struggle to save a culture that was about to be lost. In particular, the 127 articles he contributed to the Encyclopedia of Islam, published by the Religious Foundation of Türkiye, are invaluable in making the Ottoman heritage in Europe visible and well-documented.

Kiel’s life was spent tracing the past, as if traveling through a tunnel of time. He would modestly say something like, “I am a peasant, I was born in a small village in Holland.”

He was a wise traveler who came from a small village in the Netherlands and listened to history in the narrow streets of Istanbul, Skopje, Thessaloniki, Sarajevo and Mostar. He would never write about a place he had not visited or seen. He used to say that he would not write a single line without feeling the spirit of the stone, the building, or the neighborhood.

He was also actively involved in the reconstruction of monuments destroyed during the war, mainly symbolic structures such as the Mostar Bridge. He shared his archives during the reconstruction of the Mostar Bridge because his archives were not only those of an academic, but also those of a memory, a testimony and a conscience.

He worked throughout his life to bring Ottoman civilization out of the darkness, which Western historians, in particular, had ignored. “I fight against this situation with my pen,” he once said. And indeed, with his pen, knowledge, loyalty and grace, he sought to do justice to this culture.

Kiel was a man of heart who tried to understand not only the architectural heritage of the Ottoman Empire, but also the daily life of the Turkish people, the cultural traces that permeated the provinces, the mosques, inns, fountains and tekkes; in other words, our living memory. However, he also photographed and documented the heritage of Christian communities in Anatolia and the Balkans with the same meticulousness.

He is no longer with us. But the photographs he took, the data he collected live on.

He left thousands of photographs he took to the Netherlands Archaeological Institute in Istanbul. In the frames he captured, there were not only castles, mosques, masjids, bridges, fountains, tekkes, schools, madrasas and minarets, but also the abandoned Turkish neighborhoods of the Balkans, the forgotten streets, the sad Ottoman buildings; in short, the traces of an entire civilization trying to resist the passage of time. Today, by looking at his photographs, it is possible to follow, step by step, the fate of Ottoman monuments over the last 60 years.

Following M. Kiel’s proposal, in September 2011, the Netherlands Institute for Research on Türkiye (NIT) launched not only a digital archive project but also a rescue initiative aimed at preserving our cultural memory. The photographic archive of Ottoman architecture created by Machiel Kiel between 1960 and 1990, with patience, labor, and a profound sense of history, was digitized and made accessible.

This archive is perhaps the only remaining visual record of hundreds of buildings that have since been demolished, destroyed, or rendered unrecognizable. Each frame Kiel captured is not just a photograph; it is the silent memory of an era, a civilization and a geography.

Today, it means more than ever that all of these images are now available to the public and researchers in their entirety, in that they are no longer just part of an academic archive; they have now become a rare record of a vanishing past. To see through Machiel Kiel’s eyes is to see the Ottoman traces across Europe anew.

And this precious heritage, while being meticulously preserved today, deserves to be carried forward into the future.

M. Kiel showed us a new way of understanding stones. And now, after a life as solid and enduring as stone, the most fitting tribute for him is clear: an elegant, dignified and straightforward tomb in the Ottoman style.

For he was never a stranger to this civilization, but a beloved companion.

May your soul rest in peace, our dear teacher. Not only the Turks or the Dutch, but also history itself will never forget you.