Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

During the judicial recess of the past three months, several cases have emerged in which detentions were extended, as seen with Fatih Altaylı and Furkan Karabay, or judicial control measures were not lifted, as in the cases of Elif Akgül and Ender İmrek.

The BİA Media Monitoring Report for the July-August-September 2025 period reveals that, in an environment where the authoritarian regime has instrumentalized the judiciary for its own purposes, favorable rulings by the Constitutional Court (such as those involving Murat Aksoy, Evrensel, etc.) and occasionally by the Court of Cassation (as in the cases of Cem Şimşek, Ahmet Ayva, etc.) that uphold the rights to journalism and criticism now hold little significance or transformative power beyond offering “partial redress.”

While the European Union has taken steps to improve media pluralism, public broadcasting, social media platforms, and copyright regulations through initiatives like the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) and the Digital Services Act, authorities in Turkey are failing to take responsibility for regulating the journalism sector in the age of Artificial Intelligence. Turkey ranks 159th among 180 countries in the 2025 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

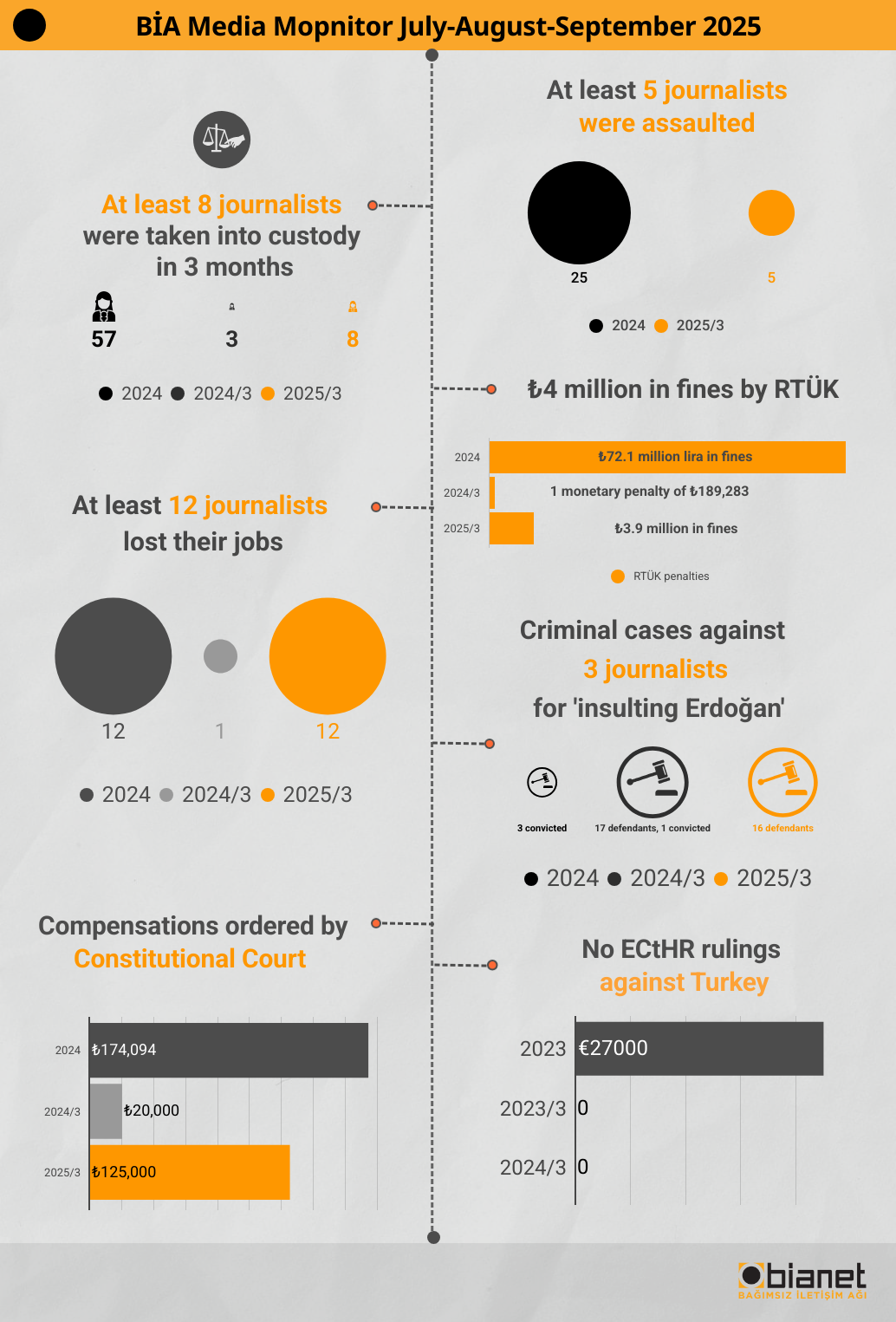

In Turkey, the arbitrary detention of journalists continues to seriously harm press freedom. Over the past three months, journalists Fatih Altaylı and Furkan Karabay were arrested over their YouTube broadcasts, Ercüment Akdeniz over an investigation into the Peoples’ Democratic Congress (HDK), and Can Taşkın in Nevşehir over two articles he wrote.

Five staff members of LeMan magazine were also detained under violent conditions following interventions by government officials including the president and the justice minister. They were arrested on charges of “inciting hatred and enmity among the public.” Four were released under judicial control, while the detention of cartoonist Doğan Pehlevan was extended.

Over the past three months, four journalists were taken into custody, and the practice of forcibly bringing journalists to testify under police escort has also drawn attention.

Journalist Timur Soykan was detained over a social media post stating, “The coup continues. The will of the people is being hijacked. Elections no longer mean anything.” Tolga Şardan, a columnist for the news site T24 who questioned the reliability of electronic signatures, TELE1 Editor-in-Chief Merdan Yanardağ, program host Musa Özuğurlu, and responsible editor İhsan Demir were also taken to courthouse by police force to give statements.

The Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK), whose president Ebubekir Şahin frequently targets critical broadcasting with public remarks, has brought critical channels like Sözcü TV, Halk TV, and TELE1 to the brink of losing their licenses for allegedly lacking “impartiality.” While Şahin defended the five-day broadcasting ban imposed on TELE1, RTÜK member İlhan Taşcı, who opposed these penalties, said, “What they want is for the truth not to be spoken; their goal is to silence the media and plunge the screens into darkness.”

After targeting journalist Fatih Altaylı’s YouTube channel, RTÜK most recently issued a warning to BirGün TV over licensing. It also imposed a total of 3,999,831 liras in administrative fines on television outlets for their news and program broadcasts.

In the past three months, at least five journalists—four in Mersin and one in Elazığ—were physically attacked, as was the Evrensel newspaper office in İzmir. BirGün reporter İsmail Arı and JinNews reporter Şehriban Aslan received death threats. These incidents reflect a long-standing pattern in which attacks on journalists have become normalized by authorities.

The case of investigative journalist Uğur Mumcu, who was assassinated with a bomb placed under his car, continues to illustrate the scale of impunity for crimes against journalists in Turkey. Oğuz Demir, the bomber, has supposedly been on Interpol’s wanted list for 32 years. Former Interior Minister Mehmet Ağar, who held office at the time, appeared in court 32 years later as a witness, admitting his helplessness. The state only now, after more than three decades, is formally reaching out to security institutions to search for the bomber.

Although no new convictions for “insulting the president” were recorded in the past three months, new journalists have been added to the list of those facing trial, including Mehmet Tezkan, İbrahim Kahveci, and Suat Toktaş. Meanwhile, the Court of Cassation overturned lower court rulings that had sentenced Evrensel newspaper’s Cem Şimşek and journalist Ahmet Ayva under the same charge.

Article 299 of the Turkish Penal Code (TCK) has provided the legal basis for the prosecution of more than 250 journalists during President Erdoğan’s 11 years in office. At least 79 of them have received prison or monetary penalties—some with deferred sentences. Unfortunately, neither the 2016 recommendation of the Venice Commission nor the European Court of Human Rights’ (ECtHR) October 2021 ruling against Turkey in the “Vedat Şorli” case has prevented journalists from continuing to face arbitrary lawsuits.

In the last three months, at least 12 journalists—İsmail Arı, Melisa Gülbaş, Barış Pehlivan, Barış Terkoğlu, İbrahim Aydın, Uğur Koç, Yaşar Gökdemir, Ferhat Çelik, Osman Akın, Furkan Karabay, Baransel Ağca, and A. Zeki Üçok—have stood trial for “insult” or “insulting a public official” in cases filed upon complaints by powerful figures.

Complainants in these cases included İstanbul Chief Public Prosecutor Akın Gürlek, Turkuvaz Media Group Deputy Chair Serhat Albayrak, Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) Mersin deputy and Nişantaşı Education Foundation founder Levent Uysal, İstanbul Chief Public Prosecutor Şaban Yılmaz, Anadolu Chief Public Prosecutor İsmail Uçar, İstanbul Deputy Chief Public Prosecutor Mehmet Yılmaz, former Ankara Chief Public Prosecutor and current Court of Cassation member Yüksel Kocaman, Boğaziçi University Rector Naci İnci, and Boğaziçi University Computer Engineering Department lecturer Dr. Mehmet Turan.

While European Union countries have recently advanced regulations to protect public broadcasting and digital media rights—such as the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) and the EU Digital Act—Turkey continued to pursue the removal of many news articles from the digital space during the July–September period.

Although the Constitutional Court annulled the practice of online censorship based on “personal rights” on Oct 10, 2024, authorities have continued this censorship under the justification of “national security and public order,” even when the content relates to issues such as corruption or misconduct.

Over the past three months, Criminal Judgeships of Peace and the Information and Communication Technologies Authority (BTK) have imposed access bans on at least 46 news reports published online. These included content about jailed İstanbul Metropolitan Municipality (İBB) Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, Cengiz Holding, and Can Holding, citing “national security” or “public order” concerns.

Censorship also targeted the YouTube channels of exiled journalist and writer Can Dündar and detained journalist Fatih Altaylı, the X account of Günay Aslan, and the websites of MedyaRadar and LeMan magazine. News articles related to the son of presidential communications director Fahrettin Altun were also affected by bans during this period.

Authorities resorted to bandwidth throttling to restrict access to platforms like X, YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, and WhatsApp during the police blockade of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) İstanbul provincial headquarters.

Journalist and media ombudsman Faruk Bildirici issued a serious warning about the freedom of journalists traveling on the same plane as the president. He revealed that journalists are required to submit their questions for approval before the plane takes off, undermining their right to ask freely.

The Constitutional Court ruled that the rights to press freedom and freedom of expression of journalist Murat Aksoy were unlawfully violated. Aksoy had been unjustly detained during the coup attempt period and was later sentenced to one year and 13 months in prison.

The court also ruled that the public broadcaster TRT had unjustly won a compensation case against Evrensel over a news article. In both cases, the Constitutional Court ordered the government to pay a total of 125,000 liras in compensation, including court costs, to Aksoy and Evrensel. (EÖ/HA/VK)