Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

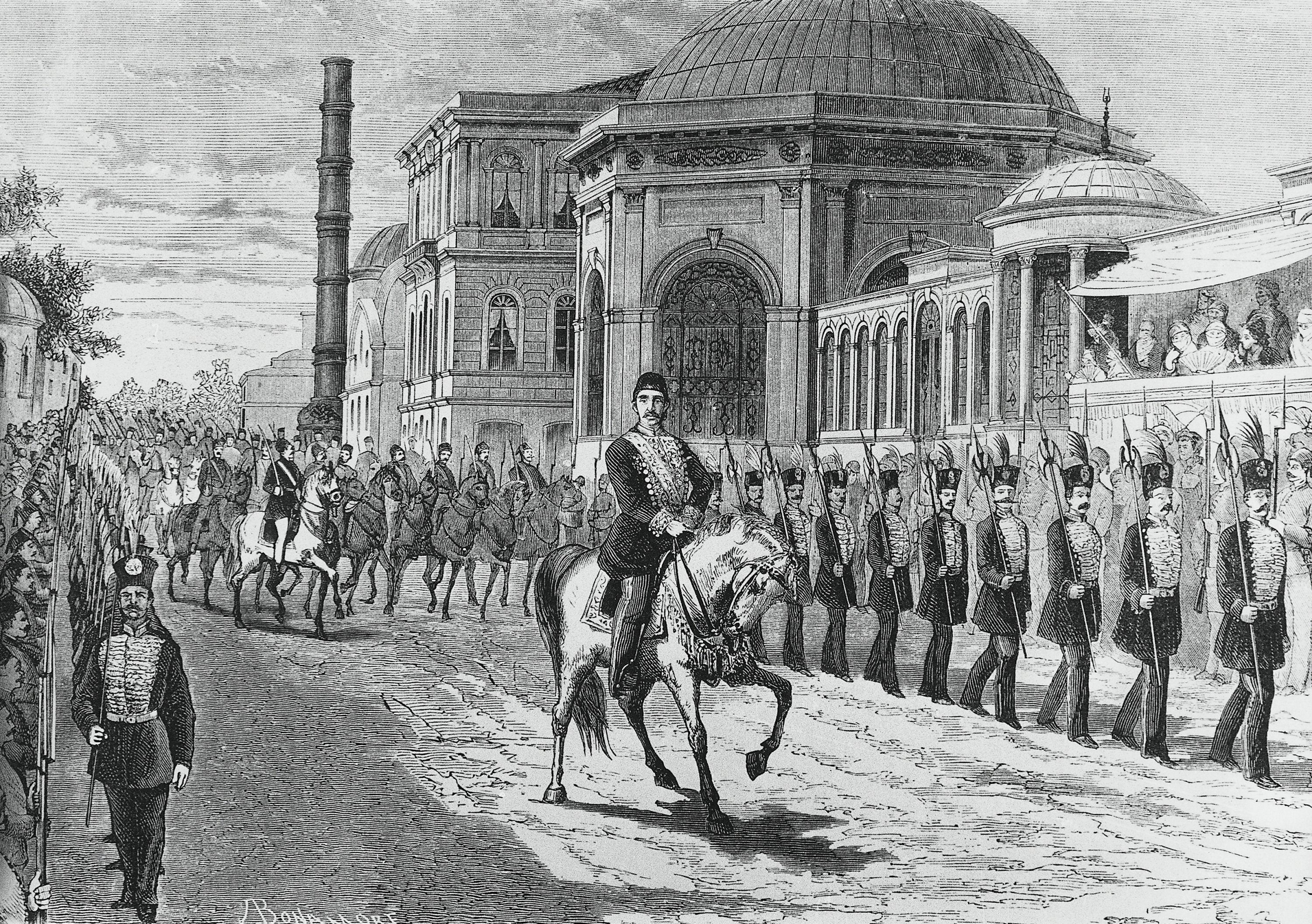

Despite facing extensive criticism, Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II played a crucial role in the transition to the republic. On the one hand, through his investments, new projects and political strategies, he slowed the long-standing territorial and geopolitical decline of the Ottoman Empire against Europe, buying valuable time. On the other hand, he launched a vast investment initiative – from education to communication, from transportation to all forms of infrastructure – that made it possible to envision a new beginning. For the first time, Anatolia encountered comprehensive investments such as educational institutions, hospitals, postal and telegraph lines, railways and clock towers during Abdülhamid’s reign. Had it not been for his efforts, the Ottoman Empire could not have endured as long as it did, nor would it have been possible to establish the new republic with its necessary human capital and foundational investments.

The “Tribal School” (“Aşiret Mektebi”) project was also one of Abdülhamid II’s significant initiatives in this context. In his book “Aşiret Mektebi: Osmanlı Eğitim Tarihinde Bilinmeyen Bir Girişim” (“The Tribal School: An Unknown Initiative in Ottoman Educational History”), Mehmet Ali Neyzi sheds light on this lesser-known but important project – its purpose, the students who attended, the tribes of the Ottoman geography, and the career paths and life stories of its graduates.

As Neyzi notes, Abdülhamid II attached special importance to strengthening Ottoman-Arab relations as part of imperial recovery: “In this new world, the Sultan understood the importance of reinforcing Ottoman-Arab relations. The telegraph line project from Damascus to Medina, which began in 1892, was followed by the construction of the Hejaz Railway in 1900. Believing that the agricultural potential of the Middle East could generate significant tax revenues, the Ottomans took important steps in this area; the Sultan even purchased large tracts of land in his own name to establish model farms.”

The Tribal School was a project directed toward the same goal. Although it was originally planned to strengthen the emotional ties of Arab tribes with the Ottoman Empire and to meet the region’s need for military and administrative leaders from among its own people, over time its scope expanded to include the Balkans, Kurdish tribes and even the island of Java.

The Tribal School project was also an effort to counter and resist the soft-power recruitment strategies pursued by the major European states, which had long-established schools across Ottoman lands. These schools not only helped raise the educational level of foreign-linked communities above that of their Ottoman peers, but also became preferred institutions for the children of influential families within the Ottoman administration: “On the other hand, it is noteworthy that the British established a boarding school in Basra during the same period. Founded in 1918 especially for the sons of local tribal chiefs, records from the British Consulate in Basra indicate that the institution was modeled on Chief’s College in India and Gordon College in Khartoum (Sudan). Chief’s College, established in 1868 in Ambala, Punjab, for the children of prominent local leaders (Nawabs), was moved to Lahore in 1886 and is known today as Aitchison College. Likewise, Gordon College, founded in Sudan in 1902 for the sons of local leaders, continues to operate today as the University of Khartoum.” Therefore, the use of educational institutions as instruments of soft power in this region also began during Abdülhamid II’s reign.

While the Ottoman Empire was trying to understand the new paradigm emerging in Europe and attempting to recover, it also faced the risk of losing the future elite administrators of its own geography to these schools: “For the Ottomans, Western encroachment was not limited to the military and economic spheres; it was also an ideological problem. In the field of education, foreigners had surrounded the Empire from many directions. On the one hand, there were hundreds of missionary schools combining religion and science; on the other hand, the modern schools opened by Ottoman minorities significantly raised the educational level of the non-Muslim population.” Moreover, during this period, state schools were fewer in number than these foreign schools: “The fact that many Muslim families had also begun sending their children to these schools posed a serious threat to the administration. In terms of numbers, state schools were only about one-third of the missionary and minority schools. The observations of an Englishman who traveled through Ottoman territories in 1888 are highly striking: Let us imagine for a moment that Muslims sent missionaries to England, opened schools there, and presented views hostile to Christianity in those schools. Surely we would not remain silent in such a situation.”

Although the outcomes of the Tribal School would not fully manifest until many years later, the very fact that such an initiative was conceived during such a turbulent period is itself a characteristic of being a great state. As Neyzi observes, even though the period is retrospectively labeled an era of decline, it was in fact marked by tremendous efforts to resist and reclaim lost ground: “Despite all these assessments, in my view the Aşiret Mektebi is an institution that demonstrates how strong and ambitious the Ottoman Empire still was at the end of the nineteenth century. While the general perception is that the state was collapsing and bankrupt during this period, the Aşiret Mektebi stands as an example – similar to the Hejaz Railway – showing that the Ottomans were capable of developing strategic and complex projects and implementing them over the long term. Through the Aşiret Mektebi, the state was able to penetrate the most remote corners of the empire; from Van to Yemen, from Baghdad to Libya, the administrative organization mobilized young people from these regions, educated them in Istanbul, and later succeeded in assigning them to military and bureaucratic posts in their homelands.”

The curriculum of the Tribal School, which offered five years of education, is also quite noteworthy. In addition to courses on religious subjects, Turkish language and the Geography and History of the Ottoman lands held an important place in the curriculum every year. Moreover, subjects such as algebra, geometry, drawing, hygiene and criminal law were also included, while alongside Turkish, emphasis was placed on Arabic and Persian. On the other hand, to better prepare Tribal School graduates for the Ottoman administrative system, one-year special programs were established in the schools of War (Harbiye) and Civil Administration (Mülkiye) in 1896, offering flexible career pathways for interested students. Ömer Mansur, a graduate of the Tribal School who would later become prime minister of Libya, provides a detailed account of the school’s curriculum and teachers in his memoirs: “We studied Turkish, Arabic, Persian, French, Mathematics, Geography, History, and Calligraphy. Some of our teachers were religious, while others were secular. Our French teacher, Nadir Bey, and later our history teacher, Ali Nureddin, who was appointed to Benghazi, were very open-minded. Our religious sciences teacher was Kâşif Efendi, our geography teacher was Tevfik Efendi, and our geometry and drawing teacher was İbrahim Edhem Bey. Abdülmuhsin Hüseyinzade Bey, who had previously worked in Benghazi, taught Arabic. Ali Nazima Bey was both the school principal and the Turkish teacher. The calligraphy course was taught by Hamdi Bey, an artist serving at the palace.”

By admitting only a small number of students each year (around 50), the Tribal School, during its 15 years of active operation, fulfilled functions beyond meeting the military and administrative manpower needs of the Ottoman territories. It also played an important role in restoring cohesion during the period of dissolution. This becomes even clearer when examining the life stories of its graduates: “Despite all this, the approximately five hundred students who graduated from the Aşiret Mektebi received a high-level education, and the experience itself contributed to their being more successful in life. In later years, it is evident that these graduates served the Ottoman Empire in important capacities, both at the highest levels and within the military and bureaucracy.” Graduates served in many different regions of the Ottoman Empire. Among them were individuals who became district governors (kaymakam), held senior military posts, and even entered the Ottoman Parliament as the first deputies representing their regions. Similarly, among the graduates, Ömer Mansur and Sadullah Koloğlu would later become prime ministers of Libya.

This network of relationships continued even after the establishment of the Republic of Türkiye. For example, Fethi Mansur, the son of Ömer Mansur, sought to build strong ties with the Republic of Türkiye during his tenure as Minister of Justice. Owing to its significance, the newly founded Republic also wished to continue this project: “Interestingly, in 1933, the newly established Republic of Türkiye decided to open ‘mobile tribal schools.’ According to a report in the newspaper Vakit, the government prepared a program aimed at educating the Kurds. Specially selected teachers would travel through the countryside of Eastern Anatolia to educate the children of the tribes. The Prime Ministry allocated a budget for this initiative.”

In summary, the Aşiret Mektebi project, implemented during the final period of the Ottoman Empire, was Abdülhamid II’s initiative to use education as a form of soft power, and it indeed bore fruit. The structure of the curriculum, its relevance to the conditions of the time, and the emphasis on quality rather than quantity – reflected in the careful selection of students – remain instructive today. Significantly, this tradition was carried forward in the newly established Republic of Türkiye. Particularly over the past 20 years, the successful and complementary initiatives directed toward the cultural sphere of affinity – such as the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA), the Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (YTB), Türkiye Scholarships, and the schools of the Maarif Foundation – are extremely promising in demonstrating how this tradition has been transmitted to the future and how its spirit continues.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the editorial stance, values or position of Daily Sabah. The newspaper provides space for diverse perspectives as part of its commitment to open and informed public discussion.