Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

A final agreement on military and administrative integration was reached on Jan 30 between the Syrian Interim Government and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The agreement includes provisions for a ceasefire, the gradual unification of military and administrative structures, and the regulation of basic rights for Syrian Kurds.

SDF leader Mazloum Abdi announced that implementation of the agreement would begin on Monday, Feb 2. He stated that the text does not fulfill all their objectives but emphasized that the achievements gained should not be underestimated.

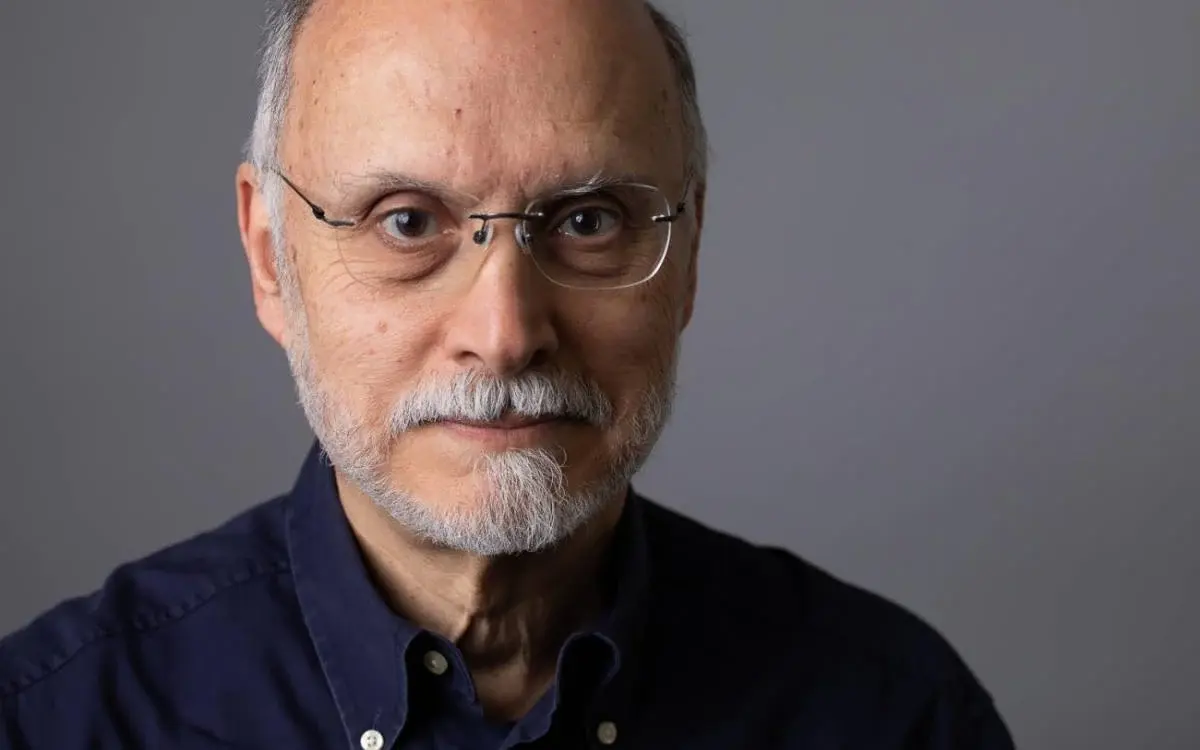

Since Jan 6, we have witnessed attacks targeting Kurds in northern and eastern Syria. We spoke with Lebanese socialist political scientist and thinker Gilbert Achcar about these attacks, the emerging “new order” in the Middle East, and the roles of the US, Turkey, and Israel within that order.

Achcar described the inability of progressive forces to fill the vacuum left by the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria as a defeat. He stressed that although the situation has become even more chaotic due to Israeli airstrikes, hope lies in the “new generation” capable of organizing in horizontal and democratic ways.

We know that you have argued that HTS is not as strong as the Taliban was. However, recent developments on the ground suggest that Ahmed al-Sharaa has grown stronger both militarily and diplomatically. Do you think this consolidation of power is sustainable?

The HTS military, now Syria’s official military, has certainly grown stronger during its first year in power, thanks to Gulf monarchies’ funding and Turkish support, as well as due to the dire economic situation prevailing in Syria, which is an incentive for many to join the new governmental armed forces. Two major challenges are still facing the new regime: one is that it needs to exert full control over the range of jihadist factions that composed its ranks until it managed to fill the vacuum left by the Assad regime’s collapse; the second is that it must confront a whole range of hostile forces. These are the Druze autonomous area, backed by Israel, in the south; the Kurdish autonomous area in the north-east, which was backed by the United States until recently and then abandoned; and finally ISIS, which is resuming its build-up, taking advantage of the end of Syrian Democratic Forces’ (SDF) control and the chaotic condition that now prevails in the territory whose control the SDF lost to the new regime’s forces.

The U.S. role in the January 6 Paris meetings has been interpreted as effectively giving a green light to an operation that worked against the Kurds. Why, in your view, did Washington withdraw its support for the SDF, and with what strategic calculations?

The alliance between the PYD-led forces and U.S. forces was against nature. In the war against ISIS, Washington needed ground forces to complement its remote warfare, as it wasn’t willing to engage troops in combat missions on the ground. The only forces with which it could cooperate in the fight against ISIS were of a nature originally inimical to the United States: leftwing Kurdish forces in Syria, linked to the PKK, the bitter enemy of the Turkish state, a U.S. ally and NATO member; and Shia militias in Iraq, linked to Iran, Washington’s and Israel’s regional enemy number one. As long as Washington needed the PYD-led forces—in other words, as long as it found no alternative to contain ISIS in northeast Syria—it maintained cooperation with them. However, with the collapse of the Assad regime, whose backers Russia and Iran limited Turkey’s intervention, the Trump administration is now relying on Damascus and Ankara to deal with ISIS. It therefore sees that the role of the PYD-led forces has “largely expired,” as U.S. regional representative, Tom Barrack, put it recently, very blatantly indeed.

As meetings were held in Paris between Israel, Syria, and the United States, Israeli officials have claimed that Israel did not “endorse” operations against the Kurds. How credible do you find this claim? What role do you think Israel is playing in Syria’s new balance of power?

Why would Israel “endorse” operations against the Kurds when Ankara stands behind them and Israel sees Turkey as a regional opponent rather than an ally? Had Washington not been involved in these events, Israel would probably have made some gesture of support to the Kurds. Not because it supports the Kurdish cause, of course, but only opportunistically, because Israel has always seen the fragmentation of the region along ethnic and religious lines as very much in its interest. That’s an old Zionist strategy. The same logic stands behind Israel’s positioning itself as a defender of the Druze in southern Syria. It has exerted much effort historically to detach the Palestinian Druze from other Palestinians, Muslim and Christian, and has treated them differently. Its present interference in supporting Druze separatism in Syria is but a continuation of this “divide and rule” policy.

In one of his recent meetings, Abdullah Öcalan is reported to have said that “Israel appears to have offered al-Sharaa the land between the Euphrates and the Tigris in exchange for Golan and Suwayda.” How do you interpret this assessment?

Israel did not need to make a deal with al-Sharaa to keep the Golan heights, which it conquered in 1967 and formally annexed in 1981, nor did it need to make a deal with him to lay its sway over the Druze region. Al-Sharaa has certainly not the power to threaten Israel. His government is much weaker than the Assad regime, especially after Israel’s wholesale destruction of Syria’s major military means right after the fall of Assad. The only reason why Israel is not interfering with what is happening in northern Syria is that Netanyahu does not want to irritate the Trump administration.

Today, Turkey’s demand that the SDF be dismantled is being articulated alongside renewed discourse about a “peace process” in Ankara. How do you think this dual approach will shape the Kurdish question in Turkey?

There is no contradiction here, of course. For Ankara, there can be no “peace” with the Kurds without the abandonment of their aspiration to regional autonomy in any form—from the aspiration to full self-determination to the reduced aspiration to democratic decentralization. The Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria is intolerable for Ankara, even if reduced to the Kurdish-majority areas of northeast Syria.

Do you see a direct connection between the ongoing attacks in Gaza and Lebanon and the emergence of a “new order” in Syria?

Israel, which is carrying on its attacks in Gaza and Lebanon, is not supportive of the “new order” in Syria. The main factor in the Assad regime’s collapse was not al-Sharaa’s Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) but Russia’s withdrawal of most of its forces from Syria after it invaded Ukraine and got bogged down in the war there, followed by Israel’s decapitation of Lebanon’s Hezbollah and destruction of much of its military potential. Combined with Israel’s direct attacks on Iran, the attack on Hezbollah rendered Tehran unable to shore up the Assad regime as it had been doing since 2013. Thus, deprived of the two pillars upon which it relied, i.e. Russia and Iran, the regime collapsed. However, instead of supporting the emergence of a “new order” in Syria, Israel has been consistently working to undermine it.

Looking at the current situation, what do you see as the most likely scenario for Syria in the near future?

I don’t think that the HTS regime will succeed in spreading its control over all of the territory that the Assad regime ruled prior to the civil war, let alone the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. The reunification of the territory, including the Druze-majority region of Suwayda and the Kurdish-majority areas in the North, would have been possible only if you had a truly democratic and secular government in Damascus, seeking consensus by truly involving all components of Syria’s population and supporting a degree of regional autonomy and decentralization. The HTS regime is seeking to spread and consolidate its control over most of Syria’s territory, except Suwayda and the Golan. Ankara will pressure the HTS regime to seek to subdue the Kurdish-majority areas in the North. Washington will exert parallel pressure on the PYD to abdicate its regional autonomy in exchange for some kind of guarantee. The PYD would be foolish to rely upon it. However, it might well find itself with no other option but to risk a military defeat at the hands of HTS forces backed by Turkish forces.

Finally, as a Lebanese Marxist, where do you locate “hope in 2026”? Which social forces and which political strategy carry that hope?

The regional situation is presently very grim in the context of a world situation that is itself quite grim. Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza, the extension of its regional power by way of heavy blows inflicted to Hezbollah and Iran, the inability of Syria’s progressive forces to fill the vacuum left by the collapse of the Assad regime and the fact that it is HTS that did so, the terrible bloodbath recently perpetrated by the theocratic regime in Iran in quelling the popular uprising, along with the inability of the opposition in Turkey to successfully resist the AKP government’s repressive onslaught—the result of all these defeats is that the region is now under the competing hegemonies of Israel and Turkey, along with the remnants of Iran’s hegemony.

My hope is that the new generation will be able to assimilate the lessons of the accumulated failures of progressive forces before them and build a credible radical democratic alternative. The overwhelming majority of the people have a stake in progressive change: short of such a change, the region will witness further descent into barbarism. So my hope is primarily based on a generational shift. The most advanced experience in the region until now was that of the young people of the Resistance Committees in Sudan. We have seen a strong aspiration to a democratic form of organization in the recent Gen Z movement in Morocco. I hope that the new generation will find a suitable combination of horizontal democratic forms of organization and political leaderships capable to clear an independent progressive path, in defense of the material and cultural interests of the people and in equal opposition to all rival reactionary poles, whether religious or “secular.” (TY/VK)