Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

Physical Address

Indirizzo: Via Mario Greco 60, Buttigliera Alta, 10090, Torino, Italy

For over 300 years, the closely guarded secrets of the Ottoman Empire’s luminous tilework were lost, but its rediscovery has revived a key part of Türkiye’s cultural heritage.

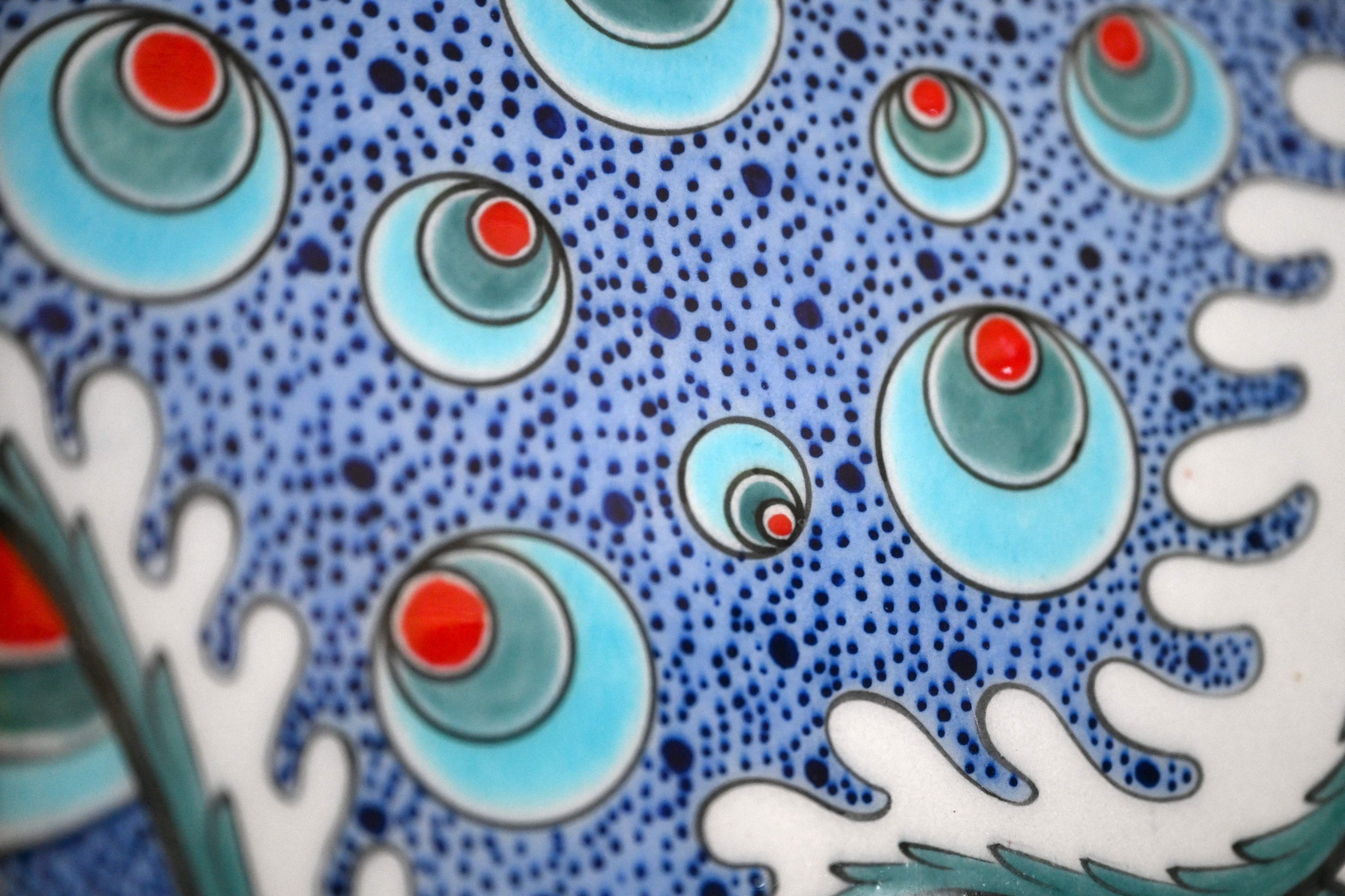

Renowned for intricate designs and lustrous colors, Iznik tiles are considered the pinnacle of Ottoman art, gracing monuments such as Istanbul’s Blue Mosque, locally known as the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, and Topkapı Palace.

The tiles come from Iznik, a small town near Istanbul with a ceramics tradition spanning two millennia, also known as Nicaea, which hosted a landmark Christian gathering in A.D. 325 that Pope Leo will celebrate when he visits this month.

Under the patronage of the Ottoman Empire, Iznik’s artisans flourished, obtaining “remarkable achievements” by the mid-16th century, said professor Ezgi Yalçınkaya, head of traditional Turkish arts at Uşak University.

They developed a high-quartz stonepaste, known as fritware, yielding a bright white background ideal for decorating, transparent glazes and vibrant colors, including a “coral red” for floral designs, which “created a distinctive new style,” she told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

But when the Ottoman Empire began to decline in the 17th century, the workshops started to close and the artisans, mainly Greeks and Armenians who knew the formula for the stonepaste, the colors and glazes, died off.

“Knowledge was passed entirely through master-apprentice relationships. The specific formulas – especially for the coral red and fritware composition – were oral secrets,” she said.

“Without documentation, the expertise died with the last masters. By the 18th-19th centuries, the technical knowledge was largely lost.”

Centuries later, an economics professor called Işıl Akbaygil, with a passion for Ottoman art, set up the Iznik Foundation in 1993.

Her research project brought together experts and academics to rediscover the lost secrets of Iznik’s prized ceramics.

“What was forgotten about isn’t so much the raw materials themselves as how they’re combined … the firing temperatures and methods to achieve the distinctive coral red,” said Kerim Akbaygil, a foundation board member and one of her sons.

“The foundation spent almost two years trying to get the right recipe, working with different universities like MIT, Princeton and Istanbul Technical University,” he said.

“It was trial and error, but we finally got it right,” he told Agence France-Presse (AFP) at the foundation’s headquarters, a rustic red-tiled building set in lush gardens lined with richly-coloured tile paths.

“Iznik tiles are the only tiles in the world that use up to 85% quartz, which we use in the raw material along with clay and silica,” he said.

They are underglazed with a high ratio of quartz, giving them a “brightness and depth that are characteristic of Iznik tiles,” he said.

Decorated with metal oxides whose colors are rendered vivid through the firing process, they are then coated with a quartz-based glaze known as “sur” – Turkish for “secret.”

Jars of colors – from vibrant cobalt blues and emerald greens to coral reds – line the shelves inside a large upper room where a dozen women sit painting tiles or transferring designs onto plain white tableware.

Many are painting an enormous mural for a train station – one of the foundation’s trademark commissions, its stunning tile facades a distinctive feature of the Istanbul metro and beyond.

Adding shadow to a giant fig leaf, Yasemin Sahin, 42, admits she’s captivated by the transformation that occurs with firing.

“I’m painting this, but I don’t know what it will look like when it comes out of the kiln after it’s glazed. It’s always a surprise, that’s the beauty of it,” she told AFP.

Three decades on, and Iznik tiles are now seen on buildings across Türkiye, from colleges to coffee shops, with the foundation’s international reach spreading from Japan to Canada.

“Back in the day, Iznik tiles were sponsored by the palace, so the only place you could see them was inside the palaces or mosques. Now that the taboo is broken,” Akbaygil said.

Yalcinkaya said the collective significance of rediscovering the lost formulas was “tremendous” and the result of extensive research by many academics and scholars.

“These efforts revived a living tradition,” she told AFP.

“Ottoman ceramicists continuously innovated from the 14th to the 20th centuries. Today’s work continues this spirit, ensuring the tradition remains alive and relevant, which is the most authentic way to preserve cultural heritage.”